Every infuriating thing on the web was once a successful experiment. Some smart person saw

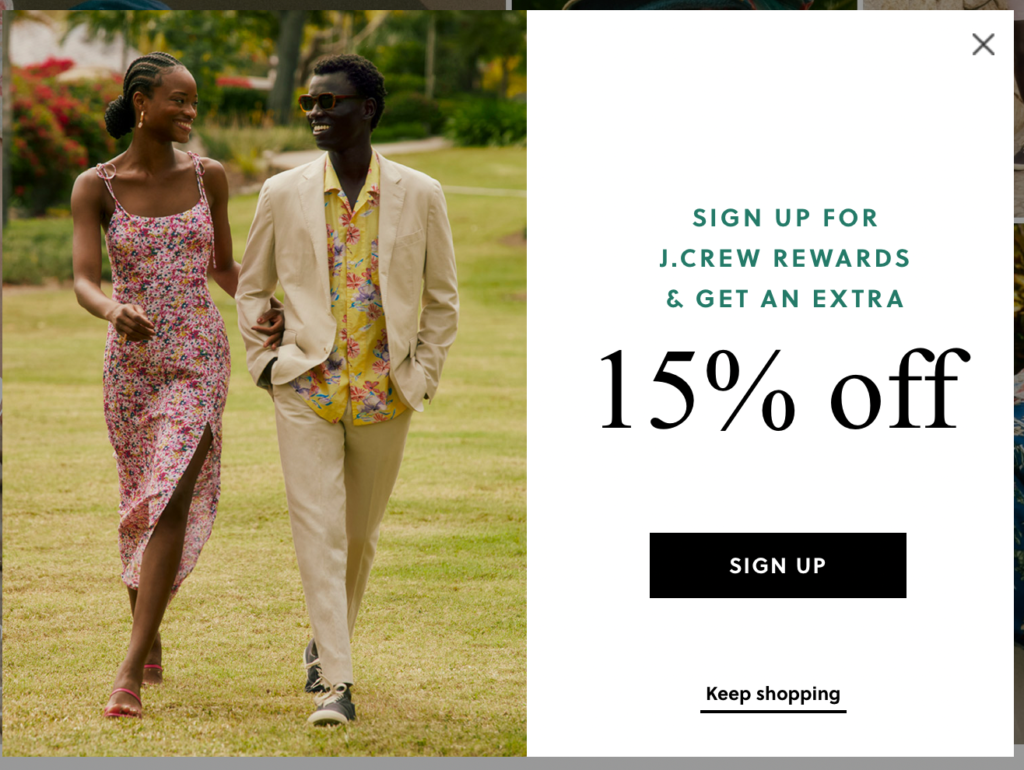

- Normal site: 1% sign up for our newsletter

- Throw a huge modal offering 10% off first order: +100% sign ups for our newsletter

…and they congratulated themselves on a job well done before shipping it.

As an experiment, I went through a list of holiday weekend sales, and opened all the sites. They all — all, 100% — interrupted my attempt to give them some money.

As an industry, we are blessed with the ability to do fast, lightweight AB testing, and we are cursing ourselves by misusing that to juice metrics in the short term.

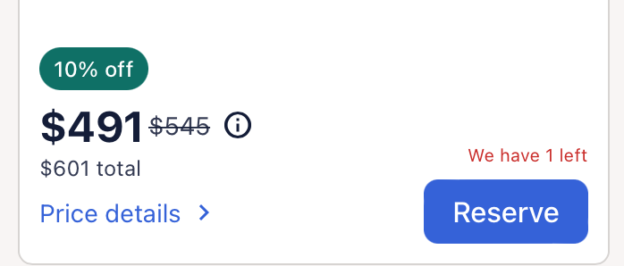

I was there for an important, very early version of this, and it has haunted me: urgency messages.

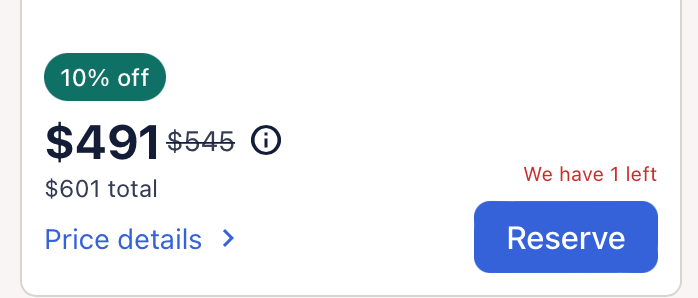

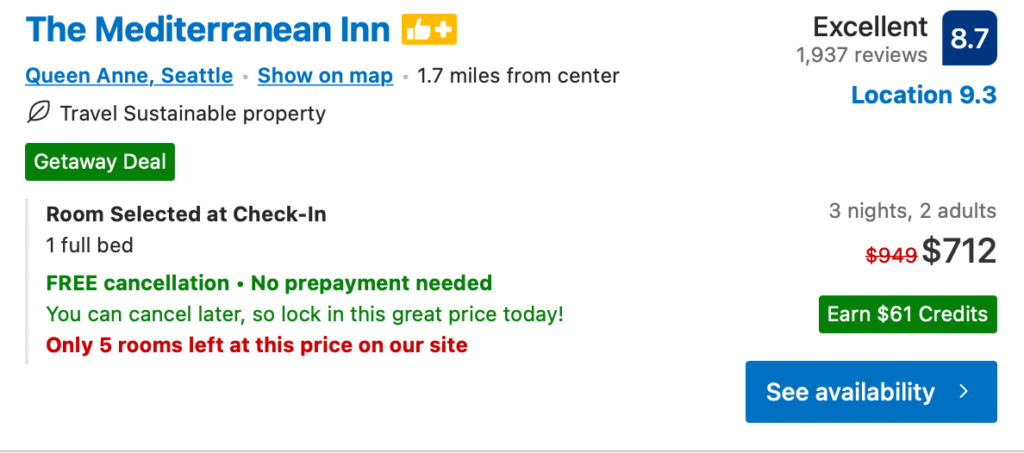

I worked at Expedia during good and bad times, and during some of the worst days, when Booking.com was an up and comer and we just could not seem to get our act together to compete. We began to realize what it must have felt like to be at an established travel player when Expedia was ascendant and they were unable to react fast enough. We were scared, and Booking.com tested something like this:

Next to some hotels, a message that supply was limited.

Why? It could be either to inform customers to make better decisions. Orrrrrr it could instill a sense of fear and urgency to buy now, rather than shop around and possibly buy from somewhere else. If that’s the last room, what are the chances it’ll be there if I go shop elsewhere?

There’s a ton of consumer behavioral research on how scarcity increases chances of getting someone to buy, so it’s mostly the second one. If a study came out that said deafening high-pitched noises increased conversion rates, we would all be bleeding from our ears by end of business tomorrow, right?

So we stopped work on other, interesting things to get a version of this up. Then Booking took it down, our executives figured it had failed A/B and thus wasn’t worth pursuing, so we returned to work. Naturally Booking then rolled it out to everyone all the time, and we took up a crash effort to get it live.

(Expedia was great to me, by the way. This just a grim time there.)

You know what happened because you see it everywhere: urgency messaging worked to get customers to buy, and buy then. Expedia today, along with almost every e-commerce site that can, still does this —

It wasn’t just urgency messages, either. We ran other experiments and if they made money and didn’t affect conversion numbers (or if the balance was in favor of making money), out they rolled. It just felt bad to watch things like junky ads show up in search results, and look at the slate of work and see more of the same coming.

I and others argued, to the more practical side, that each of those things might increase conversion and revenue immediately and in isolation but in total they made shopping on our site unpleasant. In the same way you don’t want to walk onto a used car lot where you know you’ll somehow drive off with a cracked-odometer Chevrolet Cavalier that coughs its entire drivetrain up the first time you come to a stop, no one wants to go back to a site that twists their arm and makes them feel bad.

Right? Who recommends the cable company based on how quick it was to cancel?

And yet, if you show your executives the results

- Control group: 3% purchased

- Pop-up modals with pictures of spiders test group: 5% purchased

- 95% confidence

How many of them pause to ask more questions? (And if they have a question, it’s “is this life yet why isn’t this live yet?”)

And the justifications for each of the compromises are myriad, from the apathetic to outright cynical: they have to shop somewhere, everyone’s doing it, so we have to do it, people shop for travel so infrequently they’ll forget, no one’s complaining.

There’s two big problems with this:

1) if you’re not looking at the long-term, you may be doing serious long-term damage and not know it, and you’ll spiral out of control

2) you’ll open the door to disruptive competition that you almost certainly will be unable to respond to as a practical matter

Let’s walk through those email signups as an example case.

What this tells me as a customer is they want me sign up for their email more than they want me to have an uninterrupted experience at the very least. It’s like having a polite salesperson at the store ask if you need help, except it’s every couple seconds of browsing, and the more seriously you look the more of your information they want.

They’re willing for me to not buy whatever it was I wanted, or at least they are so hungry to grow their list they’ll pay me to join, which in turn should make anyone suspect they’re going to spam the sweet bejeezus out of their list in order to make back whatever discount they’re giving out.

As a product manager, it means that company has an equation somewhere that looks like

(Average cart purchase) * (discount percentage) + (cost of increased abandon rate) > ($ lifetime value of a mailing list customer)

…hopefully.

It may also be that the Marketing team’s OKRs include “increase purchases from mailing list subscribers by 30% year over year”

So there’s some balance you’re drawing between cost of getting these emails — and if you’re putting one or two of these shopping-interrupting messages on each page, it’s going to be a substantial cost — in exchange for those emails. Now you have to get value out of those emails you mined.

You may think your communications team is so amazing, your message so good, that you’re going to be able to build an engaged customer base that eagerly opens every email you send, gets hyped for every sale, and forwards your hilarious memes to all their friends.

Maybe! Love the confidence. But everyone else also thinks that, soooooo… good luck?

As a customer, I quickly get signed up for way too many email lists, so my eyes glaze over. I’m not opening any of them. Maybe I mark them as spam because some people make it real hard to unsubscribe and it’s not worth it to see if you made opt-out easy…

Now your mailing list is starting to have trouble getting filed directly to spam by automated filters, so by percentage fewer and fewer people are purchasing based on emails. Once your regular customers have all signed up for email, subscription growth even with that incentive is slowing. And if you’re sharp, you’ve noticed the math on

(Average cart purchase) * (discount percentage) + (cost of increased abandon rate) > ($ lifetime value of a mailing list customer)

Is rapidly deteriorating, and now you’re really in trouble.

What do you do?

- Drive new customers to the site with paid marketing! It’s expensive even if you manage to target only good target customers. These new customers want that coupon, so you juice subscriptions and sales. And hey, that marketing spend doesn’t affect the equation… for a while.

- Send more emails to the people who are seeing your emails! They’re overwhelmed with emails so you need to be up in their face every day! You see increased overall purchase numbers, and way more unsubscribes/marked as spam, and people are turned off to your brand. Which also doesn’t affect that equation… for a while.

- Increase the discount offered!

- Well everyone, it’s been a good run here, I’ve loved working with you all, but this other company’s approached me with this opportunity I just can’t pass up…

This is true of so many of these: if you think through the possible longer-term consequences of the thing you’re testing, you’ll see that your short-term gains often create loops that quickly undo even the short-term gain and leave you in a worse position than when you started.

But no one tests for that. The kind of immediate, hey why not, slather Optimizely on the site and start seeing what happens testing will inevitably reveal that some of the worst ideas juice those metrics.

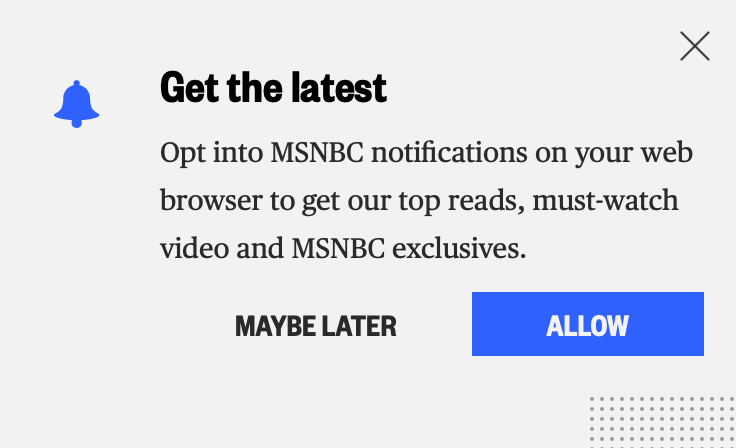

How many executive groups will, when shown an AB test for something like “ask users if we can turn on notifications” showing positive results that will juice revenue short-term, ask “can we test how this plays out long-term?”

As product managers, as designers, as humans who care, it is our responsibility to never, ever present something like that. We need to be careful and think through the long-term implications of changes as part of the initial experiment design and include them in planning the tests.

If we present results of early testing, we need to clearly elucidate both what we do and don’t know:

“Our AB test on offering free toffee to shoppers showed a 2% increase in purchase rate, so next up we’re going to test if it’s a one-time effect or if it works on repeat shoppers, whether our customers might prefer Laffy Taffy, and also what the rate of filling loss is, because we might be subject to legal risk as well as take a huge PR hit…”

Show how making the decision based on preliminary data carries huge risks. Executives hate huge risks almost as much as they like renovating their decks or being shown experiment results suggesting there’s a quick path to juicing purchase rates. At the very least, if they insist on shipping now, you can get them to agree to continue AB testing from there, and set parameters on what you’d need to see to continue, or pull, the thing you’re rolling out.

It’s not just the short-term versus the long-term consequences of that one thing, though. It’s the whole thing, all of them, together. When you make the experience of your customers unpleasant or even just more burdensome, you open the door for competition you will not be able to respond to.

I’ll return to travel. You make the experience of shopping at any of the major sites unpleasant, and someone will come along with a niche, easy-to-use, friendly site, probably with some cute mascot, and people will flock to it.

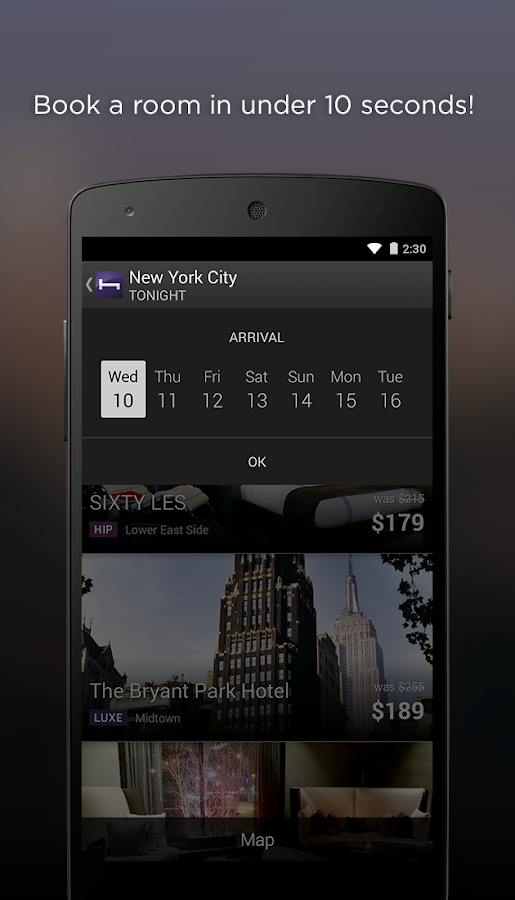

Take Hotel Tonight — started off small, slick, very focused, mobile only, and they did one thing, and you could do it faster and with less hassle than any of the big sites.

You’re paying for customer acquisition, they’re growing like crazy as everyone spreads their word for free. It’s so easy and so much more pleasant than your site! They raise money and get better, offer more things, you wonder where your lunch went…

If you’re a billion-dollar company, unwinding your garbage UX is going to be next to impossible. The company has growth targets, and that means every group has growth targets, and now you’re going to argue they should give up something known to increase purchase rates? Because some tiny company of idiots raised $100m on a total customer base that is within the daily variance of yours?

I’ve made that argument. You do not win. If you are lucky, the people in that room will sigh and give you sympathetic looks.

They’re trying to make a 30% year-over-year revenue growth target. They’re not turning off features that increase conversion. Plus they’ll be somewhere else in the 3-5 years it takes for it to be truly a threat, and that’s a whole other discussion. And if they are around when they have to buy this contender out, that’s M&A over in the other building, whole other budget, and we’ll still be trying to increase revenue 10% YoY after that deal closes.

There are things we can try though. In the same way good companies measure their success against objectives while also monitoring health metrics (if you increase revenue by 10% and costs by 500%, you know you’re going the wrong way), we should as product managers propose that any test have at least two measurable and opposed metrics we’re looking at.

To return to the example of juicing sales by increasing pressure on customers — we can monitor conversion and how often customers return.

This does require us to start taking a longer view, like we’re testing a new drug, as well — are there long-term side-effects? Are there negative things happening because we’re layering 100 short-term slam-dunk wins on top of each other?

I’m less sure then of how to deal with this.

I’d propose maintaining a control experiment of the cleanest, fastest, most-friendly UX, to use as a baseline for how far the experiment-laden ones drift, and monitor whether the clean version starts to win on long-term customer value, and NPS, as a start.

From there, we have other options, but all start from being passionate and persistent advocates for the customer as actual people who actually shop, and try to design our experiments to measure for their goals as well as our own.

We can’t undo all of this ourselves, but we can make it better in each of our corners by having empathy for the customer and looking out for our businesses as a whole. And over the long term, we start turning AB testing back into a force for long-term

…improvement.

I enjoyed this article very much. It is so true and yet hard to see when you are inside that machinery’ producing win after win. I think you are 100% right. I’ll see if I can learn from this and make a change for the better in my next endeavor.

I think you might missing a big part of why some companies started to clean up their acts. It was not out of the kindness of their hearts or a love of user experience. A lot of recent changes came under threat of unlimited fines by UK regulators:

https://www.bbc.com/news/business-44633411

Almost 3 years later, more relevant than ever. Great article! 🙂